Kenya

On the 24 July 2019 a NAP was published by the Attorney General. In April 2021, a final NAP was approved the cabinet (with some minor changes compared to the 2019 version). The formal timeperiod contained for actions in the NAP ran until the end of 2025.

It is understood that a second NAP is being considered, but there has been no formal commitment.

Available NAPs

Kenya: 1st NAP (2020-2025)

Status

On the 24 July 2019 a NAP was published by the Attorney General. In April 2021, a final NAP was approved the cabinet (with some minor changes compared to the 2019 version).

The NAP was presented to Parliament in July 2021. This is understood to be a form of disseminating the NAP among parliamentarians rather than a formal approval step.

Process

The Kenyan government announced its intention to develop a National Action Plan on Business and Human Rights on 9 February 2016.

The Department of Justice lead the process under the Attorney General’s Office and in collaboration with the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights and the NGO Kenya Human Rights Commission. A National Steering Committee whose members come from the government, private sector, and non-governmental organisations (including the United Nations) supported the process.

In Kenya, the Department of Justice led the process to develop a NAP (published in 2019 and formally adopted by the Cabinet of the Republic in 2021). A National Steering Committee (NSC) was established as the main coordinating organ and was co-chaired by the Department of Justice and the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights (Kenya’s national human rights institution). Its mandate was to provide overall strategic guidance and direction for the development of the NAP. Membership of the National Steering Committee included:

- State Law Office and the Department of Justice;

- Kenya National Commission on Human Rights;

- National Gender and Equality Commission;

- Ministry of Labour and Social Protection;

- Ministry of Energy and Petroleum;

- Central Organization of Trade Unions;

- Kenya Human Rights Commission;

- Federation of Kenya Employers;

- Kenya Private Sector Alliance;

- Global Compact Network Kenya;

- Council of Governors;

- Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights; and

- Institute for Human Rights and Business (they withdrew from the National Steering Committee during the NAP development process).

The National Steering Committee was supported by a standing secretariat housed at Kenya National Commission on Human Rights, which conducted the day-to-day NAP activities such as drafting key documents, maintaining records and organising meetings. Thematic working groups also worked on background papers to inform the NAP. By adopting a mostly consensual approach to decision-making, the steering committee aimed to ensure a reliable environment for all stakeholders to develop the NAP.

Kenya adopted the five-phase process outlined in Guidance issued by the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights. The five-phases are: 1) initiation; 2) assessment and consultation; 3) drafting; 4) implementation; and 5) update. They formed the basis of Kenya’s NAP roadmap. The entire process was expected to take eighteen months, with an initial expected completion date of June 2018.

Following initiation in February 2016, a consultation phase commenced in April 2016, with briefings for the National Steering Committee Steering and other stakeholders. There were efforts to align the NAP with the SDGs and to enhance coordination between the NAP process and the national SDG mainstreaming process, although the final NAP is not strongly SDG focused.

The process had financial support from the Kenyan government, the Kingdom of Norway (through the Norwegian Embassy in Nairobi) and the United States of America (through the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labour (DRL)).

On the 24 July 2019 a NAP was published by the Attorney General. In April 2021, the NAP was presented to cabinet which approved a final NAP (with some changes from the 2019 version). At this stage the NAP was ‘formally adopted’. The NAP as approved by the cabinet is available here. The NAP has been presented to Parliament where it remains as of July 2021. This is understood to be a form of disseminating the NAP among parliamentarians rather than a formal approval step.

In 2020, the Danish Institute for Human Rights published a case study that outlines and reflects upon the process of developing the Kenyan National Action Plan on Business and Human Rights. The case study charts the journey from the initial stages when the Government of Kenya officially committed to developing a NAP, to the current state of play with the NAP having been finalised, awaiting adoption and further action by the relevant actors, for implementation. This case study documents lessons learned – including good practices and challenges – from the Kenya NAP institutional framework and consultation process. This video examines the key elements of the development process and lessons learned:

Stakeholder Participation

In Kenya, an initial mapping of rights-holders and other stakeholders to participate in the NAP process was conducted based on the 2017 Human Rights and Business Country Guide for Kenya. Through an analysis of human rights impacts of businesses in Kenya, the following groups were identified as being vulnerable to human rights impacts of business and prioritised to ensure they were included:

- Women;

- Persons Living with Disabilities;

- Persons Living with HIV/AIDS;

- Persons Living with Albinism;

- Sexual minorities;

- Religious minorities;

- Migrant workers;

- Indigenous peoples.

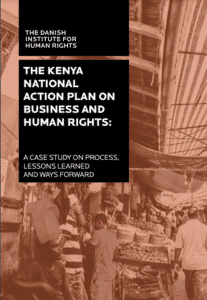

In Kenya, 9 three-day consultations with key rights-holders and other stakeholders were held at the outset of the NAP development process (by September 2017) in the locations illustrated in the map below.

The mapping of regional level participants was conducted by the government, private sector organisations, CSOs and trade unions. Participants at regional consultations included:

- Members of the public – including women and youth groups and community

- and religious leaders and some special interest groups;

- Government officials;

- Local CSOs; and

- Local businesses.

Indigenous people were separately consulted.

The multi-stakeholder sensitisation and capacity building sessions focused on the UNGPs and other relevant human rights standards and were held before the substantive part of stakeholder consultations with the aim to guarantee their effective participation. The 9 regional consultation included an initial awareness-raising session on the UNGPs and other human rights frameworks. Designing the consultations with an initial capacity-building session was seen as a positive lesson learned from the Kenya NAP process.

Additionally, targeted consultations were planned with business leaders later in 2017.

Priority areas were selected based on deliberations with stakeholders at the initial briefing stage and from a non-scientific survey of the common areas of tension between business and human rights in Kenya. These included:

- Kenya’s experience with business and human rights;

- Land and natural resources;

- Revenue transparency;

- Environment;

- Labour;

- Accountability.

The structure of each consultation included an awareness raising session introducing the UNGPs framework and other human rights frameworks (national, regional and international). Using participatory methodology, participants identify issues of concern, possible solutions, and responsible actors. Information gathered over the cause of the consultations was then synthesised into reports that will be collectively analysed and provide a basis for formulating the NAP.

An additional structure put in place to support the NAP formulation is ‘thematic working groups’. There is one working group for each thematic area, which in turn comprises subject matter experts. The thematic working groups helped deepen analysis of issues, sharpen recommendations or action points and suggest monitoring mechanisms.

Transparency

In order to identify key stakeholders and give transparency to the process, Kenya conducted a Stakeholder Forum on the Development of a NAP in late 2016.

The Kenya National Commission on Human Rights has created a website for sharing relevant information and documents.

The website presents an opportunity for continuous engagement during and after the process. Continuous updating will ensure that it serves that purpose.

National Baseline Assessment (NBA)

• Published in July 2017 and available here.

• Commissioned by the State (Office of the Attorney General and Department of Justice) to inform the development of an inaugural BHR NAP, which was published in July 2019 and approved by the cabinet in April 2021. Funded by the DIHR.

• Conducted by the National Human Rights Institution (the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights).

• Utilised the DIHR/ ICAR National Baseline Assessment Template. Based on desktop research and stakeholder consultations. Contains recommendations.

Follow-up, monitoring, reporting and review

The NAP provides in Chapter 4 that:

“To ensure that the measures proposed in this NAP are implemented, there shall be a NAP steering committee overseen by the Department of Justice and the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights.”

Establishment of NAP implementation committee

In October 2021, the Implementation Committee for the National Action Plan on Business and Human Rights (NAP) was established and undertook a 4 day induction. The key mandate of the NAP Implementation Committee is to oversee the implementation of the policy actions in the NAP. The Committee is comprised of 18 institutions drawn from government, civil society and business associations and is responsible for coordinating NAP implementation. It meets on quarterly basis. The Implementing Committee consists of representatives from:

- Office of the Attorney General & Department of Justice

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs

- National Treasury

- State Department of Gender

- Kenya National Commission on Human Rights

- Federation of Women Lawyers – Kenya

- Centre for Minority Rights Development

- Ministry of Trade and Industrialisation

- Kenya Association of Manufacturers

- Global Compact Network Kenya

- Kenya National Chamber of Commerce and Industry

- Federation of Kenyan Employers

- National Environment Management Authority

- Public Procurement Regulatory Authority

- National Council on Administration of Justice

- National Council for Children Services

- National Gender & Equality Commission

- Central Organization of Trade Unions – Kenya

NAP Implementation Plan 2021-2025

This implementation Plan includes the policy actions as set out in the NAP, the strategic activity that Government will undertake to implement the policy action, Indicators to track progress of implementation, specific government actors who are key in the implementation of the policy actions, partners, timelines and an estimated budget.

Stakeholders views and analysis on the NAP

Kenya National Commission on Human Rights: The National Action Plan on Business and Human Rights in Kenya

Institute for Human Rights and Business: Lessons Learned on Building Better National Action Plans on Business and Human Rights, April 2016

Additional resources

Danish Institute for Human Rights, The Kenya national action plan on business and human rights – a case study on process, lessons learned and ways forward (November 2020)

In 2016, a Human Rights and Business Country Guide on Kenya was developed by the Danish Institute for Human Rights (DIHR) and the Kenya Human Rights Commission (KHRC). The guide provides country-specific guidance to help companies respect human rights and contribute to development. The Country Guide is a compilation of publicly available information from international institutions, local NGOs, governmental agencies, businesses, media and universities, among others. International and domestic sources are identified on the basis of their expertise and relevance to the Kenyan context, as well as their timeliness and impartiality.

In 2016, a Human Rights and Business Country Guide on Kenya was developed by the Danish Institute for Human Rights (DIHR) and the Kenya Human Rights Commission (KHRC). The guide provides country-specific guidance to help companies respect human rights and contribute to development. The Country Guide is a compilation of publicly available information from international institutions, local NGOs, governmental agencies, businesses, media and universities, among others. International and domestic sources are identified on the basis of their expertise and relevance to the Kenyan context, as well as their timeliness and impartiality.

Agriculture sector

CHAPTER TWO

SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS AND THEMATIC AREAS OF FOCUS

2.2 Kenya’s Experience with Business and Human Rights

“Key business and human rights concerns in Kenya revolve around workplace rights, local communities and business relations, human rights and sustainable land use, human rights and sustainable environment and human rights and small- and medium sized enterprises. There have been allegations of human rights abuse across many business sectors including in the agricultural sector where sexual harassment, poor housing, low remuneration and poor working conditions are common particularly in commercial farms growing tea, coffee and flowers.”

Children’s rights

CHAPTER TWO: SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS AND THEMATIC AREAS

2.2 Kenya’s Experience with Business and Human Rights

Under the social pillar of the Vision 2030, Kenya aims to build a just and cohesive society with social equity in a clean and secure environment. The Key sectors under the social pillar namely: […] youth […]

CHAPTER THREE: POLICY ACTION

3.1 Pillar 1: The State Duty to Protect

Policy Actions [Page 17]

The Government will:

viii. Develop procedural guidelines for use by businesses, individuals and communities in their negotiations for land access and acquisition. These guidelines will ensure and safeguard the participation of […] youth, children [….]

3.3. Pillar 3: Access to Remedy

Policy Actions

A) State-based judicial and non-judicial remedies [Page 21]

The Government will:

vii. increase the capacity of the labour inspection department to handle labour related grievances, including through:

- increasing the number of labour inspectors to monitor and enforce compliance with labour standards by businesses, with particular attention to the implementation of mandatory policies to prevent and address […] prohibition of child labour […]

B) Non- State-based Grievance Mechanisms [Page 21]

Policy Actions

The Government will:

- Develop and disseminate guidance for businesses on the establishment of credible operational-level grievance mechanisms that are consistent with international standards. Such grievance mechanisms should be responsive to the needs and rights of vulnerable groups such as.[…] children […]

CHAPTER FOUR: IMPLEMENTATION AND MONITORING [Page 22]

To ensure that the measures proposed in this NAP are implemented, there shall be a NAP Steering Committee overseen by the Department of Justice and the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights. The Implementing Committee will consist of representatives from the following institutions: […]

14. National Council for Children Services

Conflict-affected areas

Construction sector

Corporate law & corporate governance

| CHAPTER TWO: SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS AND THEMATIC AREAS OF FOCUS

2.4 Revenue Transparency [page 9] [T]he NAP consultations identified several challenges that affect revenue transparency:

CHAPTER THREE: POLICY ACTIONS 3.1. Pillar 1: The State Duty to Protect Policy Actions [Page 21] The Government will: x. Finalise the development of regulations to the Access to Information Act to facilitate disclosure of contracts, including those that have a significant economic and social impact in the country and join the Extractives Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) for the facilitation of revenue transparency;

3.2. Pillar 2: Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights Policy Actions [Page 18-19] b) Human Rights Policy commitments The Government will: i. Require businesses to adopt human rights policies, including taking measures to ensure their operations respect human rights, including by providing access to a remedy for human rights violations; d) Reporting: Enforce the requirement for businesses to prepare non-financial reports in line with the Companies Act, 2015, and encourage proactive disclosure of their impacts on human rights and the mitigation measures they are taking in this regard. |

Corruption

CHAPTER TWO: SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS AND THEMATIC AREAS OF FOCUS

2.4 Revenue Transparency [Page 9-10]

Tax justice and the regulation of financial behaviour of companies can no longer be treated in isolation from the corporate responsibility to respect human rights, outlined in the UNGPs and business commitments to support the SDGs. Indeed, the SDGs include specific targets on reducing illicit financial flows (IFFs), returning stolen assets, reduction of corruption, and strengthening domestic resource mobilisation. In this respect, Goal 16 on the promotion of peaceful and inclusive societies includes specific targets on reducing illicit financial flows (target 16.4) [and] corruption (target 16.5). […]

The 2017 amendments to the Proceeds of Crime and Anti-Money Laundering Act, 2009 establish the Financial Reporting Centre (FRC), an independent financial intelligence agency charged with combating money laundering and identifying proceeds of crime including tax evasion. The Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission Act, 2012 creates the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC) whose mandate is to combat and prevent corruption and economic crimes set out in the Anti-Corruption and Economic Crimes Act. The Bribery Act, 2016 seeks to address the supply side of corruption by placing a duty on businesses to put in place appropriate measures relative to their size, scale and nature of operations towards the prevention of bribery and corruption, and also requires any person holding a position of authority in a business to report any knowledge or suspicion of bribery within twenty-four hours. Kenya is also party to international and regional initiatives on combating bribery and corruption.

Despite the above efforts, the NAP consultations identified several challenges that affect revenue transparency:

- Corruption in the process of revenue collection and the management of public revenue. Stakeholders identified corruption in the business licensing process, the process of tax collection and public procurement attributed to both public and private sector actors.

- Lack of disclosure of contracts particularly those that have significant economic and social consequences.

- Lack of transparency in administration and management of revenues from the exploitation of natural resources including from mining and oil and gas activities.

- The absence of legal beneficial ownership disclosure aids the veil of secrecy in determining who owns and controls business entities inhibiting law enforcement’s ability to ‘follow the money’.

Data protection & privacy

| The Kenya NAP makes no reference to Data Protection & Privacy |

Development finance institutions

The Kenya NAP makes no reference to Development Finance Institutions.

Energy sector

CHAPTER TWO: SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS AND THEMATIC AREAS OF FOCUS

2.1 Introduction

Environment & climate change

| CHAPTER TWO: SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS AND THEMATIC AREAS OF FOCUS

2.2 Kenya’s Experience with Business and Human Rights [Pages 5-6] Key business and human rights concerns in Kenya revolve around workplace rights, local communities and business relations, human rights and sustainable land use, human rights and sustainable environment and human rights and small- and medium- sized enterprises. Pollution is a key environmental challenge in Kenya. It gravely affects the quality of air, land and water. Air pollution from industrial and domestic sources is a leading cause of respiratory diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung cancer, pulmonary heart disease, and bronchitis thereby adversely impacting the health of citizens. Increased industrial activity witnessed in the recent past, particularly in the extractive, agricultural and manufacturing sectors, have exacerbated the problem of pollution. Toxic and hazardous substances are widely used in Kenya particularly in the agricultural and industrial sectors. Most of these substances end up contaminating soils and water bodies, causing eutrophication and destroying aquatic life (such as fisheries) and biodiversity, including traditional agricultural crops and vegetation. In addition, exposure to these substances is likely to produce chronic and acute effects. Like many other countries in Africa, Kenya is vulnerable to illegal dumping of obsolete and banned toxic and hazardous substances.

2.5. Environmental Protection [Page 10-11] There is growing global consciousness on the impact of business on the environment. The operations of businesses such as extractives, manufacturing and infrastructure could have adverse impacts on the environment leading to morbidities or mortalities unless effectively regulated. At the international level, the right to a clean environment is enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Convention on the Rights of the Child and the African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights, all of which Kenya is a party to, among others. Various SDGs targets relate to the environment and are underpinned by human rights. At the domestic level, Article 42 of the Constitution codifies the right to a clean and healthy environment. Article 69 requires the State to ensure sustainable exploitation, utilisation, management and conservation of the environment and natural resources, including by eliminating processes and activities that are likely to endanger the environment. It also obligates every person, the definition of which includes businesses, to cooperate with state organs and other persons in the protection and conservation of the environment. Article 70 of the Constitution gives any person the right to seek redress in court if the right to a clean and healthy environment has been or is likely to be violated. The Environmental Management and Coordination Act, 1999 (EMCA) revised in 2015 and the Climate Change Act, 2016 are among the key legal frameworks concerning the protection of the environment. Under the EMCA, Kenya has also adopted the use of the Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA) as a decision making tool to help improve the environmental outcomes of the management decisions. It is mandatory that certain activities that are likely to have significant impacts on the environment are evaluated and measures spelt out to mitigate identified negative impacts prior to their being approved to commence operations. The National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) is the institution responsible for the review and approval of EIAs and Environmental Management Plan (EMP) as well as for regular auditing and monitoring of the same. The Climate Change Act, 2016 establishes the National Climate Change Council, which is mandated to provide guidelines to private entities on their climate change obligations, including their reporting requirements. Stakeholders’ consultations during the development of this NAP identified the following concerns related to the impacts of businesses on the environment: iv. Environmental pollution by business operations, including through discharge of effluent into waterways, air and noise pollution and poor disposal of solid waste, toxic and hazardous substances. These negative impacts compromise the rights to; a clean and healthy environment, health, reasonable standards of sanitation, clean and safe water. v. Loss of biodiversity due to destruction and encroachment on the natural environment for commercial purposes negatively impacts livelihoods, health and access to clean and safe water for present and future generations.

2.7. Access to Remedy [Page 14-15] One example of an avenue to access remedy is Section 3 of the Environmental Management and Co-ordination Act which provides that a person may apply to the Environment and Land Court for redress for any denial, violation, infringement of or threat to the person’s right to a clean and healthy environment on the person’s own behalf or on behalf of a group of persons or in the public interest. If the Court finds such a denial, violation, infringement or threat to have occurred, it may make any order it considers appropriate to prevent or stop any act or omission that is deleterious to the environment, compel any public officer to take measures to prevent or discontinue any act or omission deleterious to the environment, require that any on- going activity be subject to an environment audit, compel the persons responsible for environmental degradation to restore the degraded environment as far as practicable to its immediate condition prior to the damage, or provide compensation for any victim of pollution. Despite these legal protections, the community consultations conducted as part of the NAP process revealed structural and procedural barriers to access to remedy, including: iii. The cost of litigation is still high for significant sections of individuals and communities. In some lawsuits, for example, it may be necessary to summon experts such as environmental experts to testify on specific issues. Such expertise may be unavailable for the community or where available, may be very expensive for the community to secure; iv. There have been instances where human rights defenders who have lodged cases against businesses, especially land and environment grievances, have reportedly faced death threats and other forms of intimidation which they hardly report to authorities. Such hostility may instil fear in others who may wish to lodge complaints, robbing communities and individuals of the protection that the law could have offered against business-related abuses;

CHAPTER THREE: POLICY ACTIONS 3.1. Pillar 1: The State Duty to Protect Policy Actions [Page 21-22] The Government will: viii. Sensitise relevant sections of the public especially women and other marginalised and minority groups on –

3.2. Pillar 2: Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights Policy Actions [Page 18] a) Training The Government will:

3.3. Pillar 3: Access to Remedy Policy Actions A) State-based judicial and non-judicial remedies [Pages 20-21] The Government will: x. Enforce all applicable laws as well as respect internationally recognised human rights laws and standards as they relate to land access and acquisition and natural resources, environment and revenue management; […] vi. Improve access to the Human Rights Division of the High Court, Employment and Labour Relations Court and the Environment and Land Court to ensure that they are accessible avenues for remedying business-related human rights abuses. The review shall include an assessment on whether the courts are expeditious and affordable; 4.1. ANNEX 1: SUMMARY OF POLICY ACTIONS

|

Equality & non-discrimination

| CHAPTER TWO: SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS AND THEMATIC AREAS OF FOCUS

2.3. Land and Natural Resources [Page 7] The country has made strides in the legal and policy protection of women’s property rights as relates to ownership, inheritance, management and disposal. The 2009 National Land Policy amongst other provisions cites the need to protect women’s right to inherit land and the land rights of widows and divorced women. It also distinguishes the inheritance rights between married and unmarried women directing the Government to secure the rights of unmarried daughters. The Matrimonial Property Act, 2013 provides that a married woman has equal rights as a maried [sic.] man to acquire, administer, hold, control or dispose of property whether movable or immovable. The Act further provides that ownership of matrimonial property vests in the spouses according to their contribution, either monetary or non monetary [sic.], in its acquisition and upon divorce should be divided between the spouses. The Marriage Act, 2014 provides that parties to a marriage have equal rights and obligations at the time of the marriage, during and at the dissolution of the marriage. However despite these laws, there are still obstacles including cultural traditions, historical injustices and lack of awareness that inhibit women from accessing and owning their fair share of property and attendant rights. 2.6. Labour [Page 12-14] It is imperative that the labour market is regulated to ensure compliance with constitutional, legal and international standards. Several SDGs and ILO core conventions cover various aspects of working conditions including decent work and economic growth, reduction of inequality, quality education and gender equality. The SDG targets include: […] 2.3 (double the agricultural productivity and incomes of small- scale food producers, in particular women, […]); 4.5 (eliminate gender disparities in education and ensure equal access to all levels of education and vocational training for the vulnerable, including persons with disabilities, indigenous peoples and children in vulnerable situations); 5.2 (eliminate all forms of violence against all women and girls in the public and private spheres, including trafficking and sexual and other types of exploitation); and 8.5 (achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men, including for young people and persons with disabilities, and equal pay for work of equal value). Others are 8.8 (protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers, including migrant workers, in particular women migrants, and those in precarious employment), and 16.2 (end abuse, exploitation, trafficking and all forms of violence against and torture of children). Other constitutional rights related to labour include Article 30 which prohibits slavery, servitude and forced labour and Article 27 which guarantees equality and freedom from discrimination, specifically including the equal rights of women and men to opportunities in the economic sphere and the dictate that no person shall discriminate against another person directly or indirectly on grounds including sex, health status, religion, ethnic origin, disability and social origin. Several statutes give effect to these labour-related Constitutional guarantees, including those dealing with labour disputes, working conditions and protection against discrimination. During the stakeholders’ consultations the following concerns were identified: 1) Sexual harassment is widespread and underreported, with women being the majority of victims. Fear of job loss is a major factor in the reluctance to report. Furthermore there is low enforcement of the Sexual Offences Act, 2006 3) Low level of awareness on labour rights among workers (mostly women in low income or low skilled jobs) and employers; 5) Lack of publicly available statistics disaggregated by sex and other vulnerabilities that could be useful in addressing sex and other forms of discrimination in the workplace

2.7. Access to Remedy [Page 14] […] [t]here are a number of legislative provisions regulating business conduct to protect those within Kenya’s jurisdiction from business-related human rights violations. Protection against discrimination on the ground of HIV/AIDS status, for example, covers those in employment. The same applies to the protection of discrimination against persons with disabilities, women and marginalised groups..

CHAPTER THREE: POLICY ACTIONS 3.1. Pillar 1: The State Duty to Protect [Page 16-17] Policy Actions The Government will: ii. Introduce a requirement for conducting Human Rights due diligence including the particular impacts on gender before approval of licences/permits to businesses; x. Sensitise relevant sections of the public especially women and other marginalised and minority groups on –

xi. Develop procedural guidelines […that…] will ensure and safeguard the participation of women, persons living with disabilities, youth, children and other marginalised groups;

3.2. Pillar 2: Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights Policy Actions [Page 18-19] a) Training: Develop and disseminate guidance for businesses on their duty to respect human rights and the operationalisation of this duty in the Kenyan context, including the implications of their operations on the environment, gender, human rights defenders, minorities, persons living with disabilities, marginalised and other vulnerable groups to promote responsible labour practices and inclusivity.

3.3. Pillar 3: Access to Remedy Policy Actions [Page 25] A) State-based judicial and non-judicial remedies The Government will: vii. Increase the capacity of the labour inspection department to handle labour-related grievances, including through: Increasing the number of labour inspectors to monitor and enforce compliance with labour standards by businesses, with particular attention to the implementation of mandatory policies to prevent and address sexual harrassment [sic.] and violence, payment of minimum wages, equal pay for work of equal value, prohibition of child labour and non- discrimination against women, marginalised groups and minority groups; and,

ANNEX 1: SUMMARY OF POLICY ACTIONS [Page 23]

ANNEX 2: LEGISLATION PROPOSED FOR ENACTMENT OR AMENDMENT [Page 28]

|

Export credit

CHAPTER THREE: POLICY ACTIONS

Policy Actions [Page 18-19]

b) Human Rights Policy commitments

iii. Enforce compliance with human rights standards by State owned enterprises and other businesses that receive export credit and state support, including by providing access to remedy for human rights violations; […]

CHAPTER FOUR: IMPLEMENTATION AND MONITORING

ANNEX 1: SUMMARY OF POLICY ACTIONS [Page 25]

| Strategic Objective | Policy Actions | Key Actors |

| Strategic objective 2:

Enhance understanding of the obligation of business to respect human rights

|

Enforce compliance with human rights standards by State owned enterprises and other businesses that receive export credit and state support, including by providing access to a remedy for human rights violations.

|

State Corporations Advisory Committee, KNCHR

|

Extractives sector

|

CHAPTER TWO: SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS AND THEMATIC AREAS OF FOCUS 2.3 Land and Natural Resources [Pages 7-8] Additionally, Kenya has various laws and policies to ensure that communities hosting extractives projects benefit through revenues, employment of local people and utilisation of local goods and services. The NAP consultations identified the following concerns related to land, natural resource development and business:

2.4. Revenue Transparency [Pages 9-10] Despite the above efforts, the NAP consultations identified several challenges that affect revenue transparency: iii. Lack of transparency in administration and management of revenues from the exploitation of natural resources including from mining and oil and gas activities.

CHAPTER THREE: POLICY ACTIONS 3.1. Pillar 1: The State Duty to Protect [Page 18] The Government will: x. Finalise the development of regulations to the Access to Information Act to facilitate disclosure of contracts, including those that have a significant economic and social impact in the country and join the Extractives Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) for the facilitation of revenue transparency; |

Extraterritorial jurisdiction

| CHAPTER THREE: POLICY ACTIONS [Page 22]

3.2. Pillar 2: Corporate Social Responsibility to Respect Human Rights Policy Actions b) Human Rights Policy commitments ii. Encourage recruitment agencies to provide any required repatriation, legal and psychological support to migrant workers who have suffered or been subjected to abuse abroad;

CHAPTER FOUR: IMPLEMENTATION AND MONITORING [Page 23] 4.1. ANNEX 1: SUMMARY OF POLICY ACTIONS

|

Finance & banking sector

The Kenya NAP makes no reference to the Finance and banking sector.

Fisheries and aquaculture sectors

The Kenyan NAP does not make a direct or explicit reference to the Fisheries and Aquaculture sectors.

Forced labour & modern slavery

CHAPTER TWO: SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS AND THEMATIC AREAS OF FOCUS

2.6. Labour [Pages 12-13]

[…] Other constitutional rights related to labour include Article 30 which prohibits slavery, servitude and forced labour and Article 27 which guarantees equality and freedom from discrimination, specifically including the equal rights of women and men to opportunities in the economic sphere and the dictate that no person shall discriminate against another person directly or indirectly on grounds including sex, health status, religion, ethnic origin, disability and social origin.

CHAPTER FOUR: IMPLEMENTATION AND MONITORING

ANNEX 1: SUMMARY OF POLICY ACTIONS [Page 23]

| Strategic Objective | Policy Actions | Key Actors |

| Strategic Objective 1:

Enhance existing policy, legal, regulatory and administrative framework for ensuring respect of human rights by business through legal review and development of specific guidance for business |

Strengthen oversight mechanisms of recruitment agencies involved in the recruitment of Kenyans for employment in businesses abroad.

Take appropriate measures to promote safe and fair labour migration including agreements on free exchange of information, and more stringent regulation of employment agencies and explore measures for providing legal and psychosocial support services to victims of labour abuse. |

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Labour and Social Protection; National Employment Authority, COTU, FKE |

Freedom of association

| CHAPTER TWO: SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS AND THEMATIC AREAS OF FOCUS

2.6 Labour [Page 12] Article 41 of the Constitution of Kenya guarantees every person the right to fair labour practices, and confers specific rights on workers, employers and trade unions and employers’ organisations. Every worker is entitled to fair remuneration, reasonable working conditions, the right to join and participate in the activities of a trade union and go on strike as a means of advocating for their labour-related rights. Employers are entitled to form and join employers’ organisations and participate in such organisations’ programs. Trade unions and employers’ organisations are entitled to organise and form new or join existing federations. |

Garment, Textile and Footwear Sector

The Kenyan NAP does not make a direct reference to the Garment sector.

Gender & women’s rights

|

CHAPTER TWO: SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS AND THEMATIC AREAS OF FOCUS 2.2 Kenya’s Experience with Business and Human Rights [Pages 5-6] Under the social pillar of the Vision 2030, Kenya aims to build a just and cohesive society with social equity in a clean and secure environment. The Key sectors under the social pillar namely: […] gender […]. 2.3 Land and Natural Resources [Page 8] The country has made strides in the legal and policy protection of women’s property rights as relates to ownership, inheritance, management and disposal. The 2009 National Land Policy amongst other provisions cites the need to protect women’s right to inherit land and the land rights of widows and divorced women. It also distinguishes the inheritance rights between married and unmarried women directing the Government to secure the rights of unmarried daughters. The Matrimonial Property Act, 2013 provides that a married woman has equal rights as a maried [sic.] man to acquire, administer, hold, control or dispose of property whether movable or immovable. The Act further provides that ownership of matrimonial property vests in the spouses according to their contribution, either monetary or non monetary, in its acquisition and upon divorce should be divided between the spouses. The Marriage Act, 2014 provides that parties to a marriage have equal rights and obligations at the time of the marriage, during and at the dissolution of the marriage. However despite these laws, there are still obstacles including cultural traditions, historical injustices and lack of awareness that inhibit women from accessing and owning their fair share of property and attendant rights. 2.6 Labour [Pages 12-13] It is imperative that the labour market is regulated to ensure compliance with constitutional, legal and international standards. Several SDGs and ILO core conventions cover various aspects of working conditions including decent work and economic growth, reduction of inequality, quality education and gender equality. The SDG targets include: […] 3 (double the agricultural productivity and incomes of small- scale food producers, in particular women, […]); 4.5 (eliminate gender disparities in education and ensure equal access to all levels of education and vocational training for the vulnerable, including persons with disabilities, indigenous peoples and children in vulnerable situations); 5.2 (eliminate all forms of violence against all women and girls in the public and private spheres, including trafficking and sexual and other types of exploitation); and 8.5 (achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men, including for young people and persons with disabilities, and equal pay for work of equal value). Others are 8.8 (protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers, including migrant workers, in particular women migrants, and those in precarious employment), and 16.2 (end abuse, exploitation, trafficking and all forms of violence against and torture of children).

During the stakeholders’ consultation the following concerns were identified:

2.7 Access to Remedy [Pages 13-15] […] [T]here are a number of legislative provisions regulating business conduct to protect those within Kenya’s jurisdiction from business-related human rights violations. Protection against discrimination on the ground of HIV/AIDS status, for example, covers those in employment. The same applies to the protection of discrimination against persons with disabilities, women and marginalised groups.

CHAPTER THREE: POLICY ACTIONS 3.1. Pillar 1: The State Duty to Protect [Pages 16-18] Policy Actions The Government will: i. Introduce a requirement for conducting Human Rights due diligence including the particular impacts on gender before approval of licences/permits to businesses; vii. Sensitise relevant sections of the public especially women and other marginalised and minority groups on –

viii. Develop procedural guidelines for use by businesses, individuals and communities in their negotiations for land access and acquisition. These guidelines will ensure and safeguard the participation of women, persons living with disabilities, youth, children and other marginalised groups; xi. Strengthen leverage in using public procurement to promote human rights. This will involve the review of existing public procurement policies, laws and standards and their impacts with due regard to the state’s human rights obligations including women’s rights as part of the criteria; and, 3.2. Pillar 2: Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights [Page 18-19] Policy Actions a) Training: Develop and disseminate guidance for businesses on their duty to respect human rights and the operationalisation of this duty in the Kenyan context, including the implications of their operations on the environment, gender, human rights defenders, minorities, persons living with disabilities, marginalised and other vulnerable groups to promote responsible labour practices and inclusivity. c) Human rights due diligence: Require businesses to identify their human rights impacts including through conducting comprehensive and credible human rights impact assessments before they commence their operations and continuously review the assessment to ensure that they prevent, address and redress human rights violations. Such impact assessment should involve meaningful consultation with potentially affected groups and other relevant stakeholders and include particular gendered impacts. 3.3. Pillar 3: Access to Remedy A) State-based judicial and non-judicial remedies [Page 21] Policy Actions viii. Increase the capacity of the labour inspection department to handle labour-related grievances, including through:

B) Non-State-Based Grievance Mechanisms [Page 21] Policy Actions The Government will:

CHAPTER FOUR: IMPLEMENTATION AND MONITORING [Page 22] To ensure that the measures proposed in this NAP are implemented, there shall be a NAP steering committee overseen by the Department of Justice and the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights. The Implementing Committee will consist of representatives from the following institutions: […]

[…]

[…]

ANNEX 1: SUMMARY OF POLICY ACTIONS [Page 23]

ANNEX 2: LEGISLATION PROPOSED FOR ENACTMENT OR AMENDMENT

|

||||||||||||

Guidance to business

| CHAPTER TWO: SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS AND THEMATIC AREAS OF FOCUS

2.3 Land and Natural Resources [Page 7] The NAP consultations identified the following concerns related to land, natural resource development and business: […] 2. Lack of guidance on community consultations in the context of natural resources governance resulting in inadequate participation of local communities in decision making;

2.7 Access to Remedy [Pages 13-14] Most businesses have a relatively low understanding of their human rights responsibilities resulting in lack of engagement with employees, local communities and other stakeholders on how to ensure that they respect human rights and provide a remedy for violations. Business associations stated that they lack proper guidance on establishing credible operational-level grievance handling mechanisms.

CHAPTER THREE: POLICY ACTIONS 3.1. Pillar 1: The State Duty to Protect [Page 16-18] States are expected to explicitly set out expectations that all businesses in their jurisdictions, including state-owned businesses and those businesses with which they engage in commercial transactions, respect human rights through policies, laws and guidance.

Policy Actions The Government will: viii. Work with stakeholders to develop a natural resource revenue management policy and regulatory framework for administering and managing natural resource revenue paid to host communities. This framework should seek to promote equity, inclusivity and community decision-making and will include training to enhance the capacity of communities to manage their affairs. It will also serve to guide the operationalisation of mining revenue as envisaged by the Mining Act, 2016; […]

3.2. Pillar 2: Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights [Pages 18-19] The current voluntary initiatives established and adopted by business associations on different human rights issues do not have strict compliance and reporting mechanisms. They therefore fail to offer businesses that have ascribed to them the required guidance and supervision to ensure that their operations respect human rights. There is no mandatory requirement for human rights due diligence. Businesses, including state-owned enterprises, have not embraced the practice of engaging those whose rights are most likely to be impacted by their operations in any human rights due diligence. Policy Actions a) Training: Develop and disseminate guidance for businesses on their duty to respect human rights and the operationalisation of this duty in the Kenyan context, including the implications of their operations on the environment, gender, human rights defenders, minorities, persons living with disabilities, marginalised and other vulnerable groups to promote responsible labour practices and inclusivity.

3.3. Pillar 3: Access to Remedy [Page 21] B) Non-State-Based Grievance Mechanisms Policy Actions

CHAPTER FOUR: IMPLEMENTATION AND MONITORING ANNEX 1: SUMMARY OF POLICY ACTIONS [Pages 23-25]

|

|||||||||||||||

Human rights defenders & Civic space

| CHAPTER TWO: SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS AND THEMATIC AREAS OF FOCUS

2.7. Access to Remedy [Pages 14-15] Despite these legal protections, the community consultations conducted as part of the NAP process revealed structural and procedural barriers to access to remedy, including: iv. There have been instances where human rights defenders who have lodged cases against businesses, especially land and environment grievances, have reportedly faced death threats and other forms of intimidation which they hardly report to authorities. Such hostility may instil fear in others who may wish to lodge complaints, robbing communities and individuals of the protection that the law could have offered against business-related abuses; and

CHAPTER THREE: POLICY ACTIONS 3.2. Pillar 2: Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights [Pages 18-19] Policy Actions c) Training: Develop and disseminate guidance for businesses on their duty to respect human rights and the operationalisation of this duty in the Kenyan context, including the implications of their operations on the environment, gender, human rights defenders, minorities, persons living with disabilities, marginalised and other vulnerable groups to promote responsible labour practices and inclusivity.t

|

Human rights impact assessments

| CHAPTER THREE: POLICY ACTIONS

3.2. Pillar 2: Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights Policy Actions [Page 19] c) Human rights due diligence: Require businesses to identify their human rights impacts including through conducting comprehensive and credible human rights impact assessments before they commence their operations and continuously review the assessment to ensure that they prevent, address and redress human rights violations. Such impact assessment should involve meaningful consultation with potentially affected groups and other relevant stakeholders and include particular gendered impacts.

3.3. Pillar 3: Access to Remedy B) Non- State-Based Grievance Mechanisms [Page 21] Policy Actions The Government will: 3. Assist community-based organisations working on human rights issues to build their technical capacity to effectively monitor human rights impacts of businesses and advocate for individuals and communities to enforce their right to a remedy for human rights violations.

CHAPTER FOUR: IMPLEMENTATION AND MONITORING ANNEX 1: SUMMARY OF POLICY ACTIONS

|

Indigenous Peoples

| CHAPTER TWO: SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS AND THEMATIC AREAS OF FOCUS

2.3 Land and Natural Resources [Page 12-14] International human rights law guarantees against arbitrary deprivation of property and provides a standard of conduct to be followed in case of evictions. Furthermore, there are additional protections for indigenous people in recognising the unique importance, cultural and spiritual values that they attach to their lands, territories and natural resources. These guarantee land rights for indigenous people and provide protections against displacement from their lands. They also provide for consultation and consent to development projects. Several SDGs targets relate to land and natural resources. The NAP consultations identified the following concerns related to land, natural resource development and business: 5. Cultural and historical barriers to access to land by women, minorities and marginalised groups such as indigenous persons. These barriers limit these groups’ participation in and decision-making power over land-related issues; […]

2.6 Labour [Page 12] It is imperative that the labour market is regulated to ensure compliance with constitutional, legal and international standards. Several SDGs and ILO core conventions cover various aspects of working conditions including decent work and economic growth, reduction of inequality, quality education and gender equality. The SDG targets include: […] 2.3 (double the agricultural productivity and incomes of small- scale food producers, in particular […] indigenous peoples,[…] ); 4.5 (eliminate gender disparities in education and ensure equal access to all levels of education and vocational training for the vulnerable, including […], indigenous peoples […]);

CHAPTER THREE: POLICY ACTIONS 3.3. Pillar 3: Access to Remedy B) Non-State-based Grievance Mechanisms [Page 21] Policy Actions The Government will:

CHAPTER FOUR: IMPLEMENTATION AND MONITORING [Page 22] To ensure that the measures proposed in this NAP are implemented, there shall be a NAP Steering Committee overseen by the Department of Justice and the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights. The Implementing Committee will consist of representatives from the following institutions: 7. Three (3) Civil Society Organizations Representatives of persons living with disabilities, women and indigenous persons

|

Information and communications technology (ICT) and electronics sector

The Kenya NAP makes no reference to Information and communications technology (ICT) and electronics sector.

Read more about Information and communications technology (ICT) and electronics sector

Investment treaties & investor-state dispute settlements (ISDS)

CHAPTER THREE: POLICY ACTIONS

3.1. Pillar 1: The State Duty to Protect [Page 16]

[…] States are expected to guarantee policy coherence across different government agencies, thereby ensuring that different state institutions are aware of and observe the State’s human rights obligations. The State’s duty in this regard includes providing these institutions with the requisite information through training and support (horizontal coherence) while ensuring that the policies and regulatory frameworks are consistent with the state’s international human rights obligations (vertical coherence). This coherence should extend to the State’s investment treaties with other States or with business enterprises. […]

Policy Actions [Page 18]

The Government will:

xii. Review current trade and investment promotion agreements and bring them into compliance with the Constitution and international human rights standards to ensure that they are not used to facilitate illicit financial flows and tax evasion by businesses.

CHAPTER FOUR: IMPLEMENTATION AND MONITORING

ANNEX 1: SUMMARY OF POLICY ACTIONS

| Strategic Objective | Policy Actions | Key Actors |

| Strategic Objective 1:

Enhance existing policy, legal, regulatory and administrative framework for ensuring respect of human rights by business through legal review and development of specific guidance for business |

Review current trade and investment promotion agreements and bring them into compliance with the Constitution and international human rights standards and to also ensure that they are not used to facilitate illicit financial flows and tax evasion by businesses. | Ministry of Trade and Industry, KRA, Financial Reporting Centre (FRC) |

Read more about Investment treaties & investor-state dispute settlements (ISDS)

Judicial remedy

| CHAPTER TWO: SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS AND THEMATIC AREAS OF FOCUS

2.6 Labour [Page 13] During the stakeholders’ consultations the following concerns were identified: 6) Lack of effective remedies for victims of labour-related grievances resulting in high prevalence of unresolved labour-related grievances. A weak enforcement mechanism, in particular inadequate number of state labour inspectors and the lack of effective operational level grievance mechanisms were also cited as contributing factors.

2.7 Access to Remedy [Page 14] The Constitution of Kenya, 2010 adopts international law as part of the domestic law. In international human rights law, Kenya is obligated to protect those under its jurisdiction against human rights violations, including by third parties such as businesses. SDG 16.3 urges states to ‘promote the rule of law at the national and international levels and ensure equal access to justice for all’. Additionally, SDG 16.6 calls for the development of ‘effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels’. Article 20(1) of the Constitution provides that the Bill of Rights binds all persons, including businesses. Indeed, since the promulgation of the Constitution in 2010, courts have adjudged several businesses to be in violation of human rights and awarded victims varying remedies. Furthermore, there are a number of legislative provisions regulating business conduct to protect those within Kenya’s jurisdiction from business-related human rights violations. Protection against discrimination on the ground of HIV/AIDS status, for example, covers those in employment. The same applies to the protection of discrimination against persons with disabilities, women and marginalised groups. The breach of these and other relevant laws may result in administrative and judicial sanctions. Judicial avenues include the Human Rights Division of the High Court, the Environment and Land Court and the Employment and Labour Relations Court. Those dissatisfied with the decisions of these courts may appeal to the Court of Appeal with a limited right of further appeal to the Supreme Court. Administrative avenues include tribunals such as, National Environment Tribunal (adjudicates environmental cases including grievances against businesses) and the Rent Restriction Tribunal (adjudicates disputes between tenants and landlords). One may appeal the decisions of these tribunals to the High Court. One example of an avenue to access remedy is Section 3 of the Environmental Management and Co-ordination Act which provides that a person may apply to the Environment and Land Court for redress for any denial, violation, infringement of or threat to the person’s right to a clean and healthy environment on the person’s own behalf or on behalf of a group of persons or in the public interest. If the Court finds such a denial, violation, infringement or threat to have occurred, it may make any order it considers appropriate to prevent or stop any act or omission that is deleterious to the environment, compel any public officer to take measures to prevent or discontinue any act or omission deleterious to the environment, require that any on- going activity be subject to an environment audit, compel the persons responsible for environmental degradation to restore the degraded environment as far as practicable to its immediate condition prior to the damage, or provide compensation for any victim of pollution. Despite these legal protections, the community consultations conducted as part of the NAP process revealed structural and procedural barriers to access to remedy, including:

Most businesses have a relatively low understanding of their human rights responsibilities resulting in lack of engagement with employees, local communities and other stakeholders on how to ensure that they respect human rights and provide a remedy for violations. Business associations stated that they lack proper guidance on establishing credible operational-level grievance handling mechanisms.

CHAPTER THREE: POLICY ACTIONS 3.3. Pillar 3: Access to Remedy [Page 19] Access to an effective remedy guarantees victims of business-related human rights abuse with predictable avenues for complaints, adjudication of their grievances, an opportunity for the other party to present its case and a fair remedy based on the merits of the case. Additionally, it ensures that remedies are relevant and proportionate to the abuses, including orders to cease ongoing abuses. According to the UNGPs, State-based judicial and non-judicial mechanisms should be the primary avenue for accessing remedies by victims of corporate abuses. However, victims should also have access to operational-level grievance handling mechanisms established by businesses, where workers, local communities and civil society advocates acting on behalf of individuals and communities negatively impacted by businesses may lodge their complaints and receive a just outcome such as compensation, guarantee of non-repetition by the offender, apology, restitution and rehabilitation.

Policy Actions A) State-based judicial and non-judicial remedies [Page 20] The Government will: iii. Provide training and support to the judicial, administrative and oversight organs on business obligations in respect of human rights. Priority will be given to the following institutions:

iv. Improving access to information on available judicial and non-judicial mechanisms involved in the resolution of business-related abuses as a measure of promoting access to justice. Such information should be made available in all counties and provided in a manner accessible to vulnerable groups; v. Prioritise access to legal aid for victims of business-related human rights abuses, consistent with the Legal Aid Act, 2016 and the National Action Plan on Legal Aid; vi. Improve access to the Human Rights Division of the High Court, Employment and Labour Relations Court and the Environment and Land Court to ensure that they vi. Increase the capacity of the labour inspection department to handle labour-related grievances, including through:

CHAPTER FOUR: IMPLEMENTATION AND MONITORING ANNEX 1: SUMMARY OF POLICY ACTIONS [Page 25]

|

Land

| CHAPTER TWO: SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS AND THEMATIC AREAS OF FOCUS

2.3 Land and Natural Resources [Page 12-14] Land is a prerequisite for the enjoyment of economic, social and cultural rights relating to an adequate standard of living, housing, food and natural resource benefits sharing. The Constitution states that “all land in Kenya belongs to the people of Kenya collectively as a nation, as communities and as individuals”. However it is often a source of conflict due to population pressure, rapid urbanisation, environmental degradation, land-intense large-scale projects such as mining, oil and gas and commercial agriculture, all of which result in competition for available productive land. International human rights law guarantees against arbitrary deprivation of property and provides a standard of conduct to be followed in case of evictions. Furthermore, there are additional protections for indigenous people in recognising the unique importance, cultural and spiritual values that they attach to their lands, territories and natural resources.2 These guarantee land rights for indigenous people and provide protections against displacement from their lands. They also provide for consultation and consent to development projects. Several SDGs targets relate to land and natural resources3. Kenya has a relatively progressive constitutional and statutory framework for the ownership, management and access to land and natural resources found within her boundaries. The Constitution provides that land, whether public, private or communal, shall be held, used and managed in a manner that is equitable, efficient, productive and sustainable. The Constitution also guarantees the right to property, and the protection from arbitrary deprivation of one’s property including land. In addition to the Constitution, the Land Act, 2012 deals with public land under Article 62 of the Constitution, private land under Article 64 of the Constitution, and community land under Article 63 of the Constitution. Further, the Community Land Act, 2016 deals more substantively with community land which is vested in and held by communities identified on the basis of ethnicity, culture or similar community interest. All matters relating to compulsory land acquisition, including access to land for business purposes, are governed by the Land Act, 2012. The country has made strides in the legal and policy protection of women’s property rights as relates to ownership, inheritance, management and disposal. The 2009 National Land Policy amongst other provisions cites the need to protect women’s right to inherit land and the land rights of widows and divorced women. It also distinguishes the inheritance rights between married and unmarried women directing the Government to secure the rights of unmarried daughters. The Matrimonial Property Act, 2013 provides that a married woman has equal rights as a maried [sic.] man to acquire, administer, hold, control or dispose of property whether movable or immovable. The Act further provides that ownership of matrimonial property vests in the spouses according to their contribution, either monetary or non monetary, in its acquisition and upon divorce should be divided between the spouses. The Marriage Act, 2014 provides that parties to a marriage have equal rights and obligations at the time of the marriage, during and at the dissolution of the marriage. However despite these laws, there are still obstacles including cultural traditions, historical injustices and lack of awareness that inhibit women from accessing and owning their fair share of property and attendant rights. Furthermore, the Constitution guarantees access to information, community empowerment and inclusion in decision-making and benefit sharing from exploitation of natural resources. Additionally, Kenya has various laws and policies to ensure that communities hosting extractives projects benefit through revenues, employment of local people and utilisation of local goods and services. The NAP consultations identified the following concerns related to land, natural resource development and business:

2.7 Access to Remedy [Page 14-15] Article 20(1) of the Constitution provides that the Bill of Rights binds all persons, including businesses. Indeed, since the promulgation of the Constitution in 2010, courts have adjudged several businesses to be in violation of human rights and awarded victims varying remedies. Furthermore, there are a number of legislative provisions regulating business conduct to protect those within Kenya’s jurisdiction from business-related human rights violations.[…] The breach of these and other relevant laws may result in administrative and judicial sanctions. Judicial avenues include the Human Rights Division of the High Court, the Environment and Land Court and the Employment and Labour Relations Court.[…] Despite these legal protections, the community consultations conducted as part of the NAP process revealed structural and procedural barriers to access to remedy, including: […] iv. There have been instances where human rights defenders who have lodged cases against businesses, especially land and environment grievances, have reportedly faced death threats and other forms of intimidation which they hardly report to authorities. Such hostility may instil fear in others who may wish to lodge complaints, robbing communities and individuals of the protection that the law could have offered against business-related abuses; and

CHAPTER THREE: POLICY ACTIONS 3.1. Pillar 1: The State Duty to Protect [Page 17] Policy Actions The Government will: v. Expedite land adjudication and registration with a view to securing the protection of land owners/users and communities especially in areas ear-marked for major projects; vii. Sensitise relevant sections of the public especially women and other marginalised and minority groups on –

viii. Develop procedural guidelines for use by businesses, individuals and communities in their negotiations for land access and acquisition. These guidelines will ensure and safeguard the participation of women, persons living with disabilities, youth, children and other marginalised groups; ix. Work with stakeholders to develop a natural resource revenue management policy and regulatory framework for administering and managing natural resource revenue paid to host communities. This framework should seek to promote equity, inclusivity and community decision-making and will include training to enhance the capacity of communities to manage their affairs. It will also serve to guide the operationalisation of mining revenue as envisaged by the Mining Act, 2016;

3.3. Pillar 3: Access to Remedy Policy Actions A) State-based judicial and non-judicial remedies [Pages 19-20] The Government will: i. Enforce all applicable laws as well as respect internationally recognised human rights laws and standards as they relate to land access and acquisition and natural resources, environment and revenue management;

CHAPTER FOUR: IMPLEMENTATION AND MONITORING ANNEX 1: SUMMARY OF POLICY ACTIONS

|

Mandatory human rights due diligence

| CHAPTER TWO: SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS AND THEMATIC AREAS OF FOCUS

2.2 Kenya’s Experience with Business and Human Rights [Pages 6-7] To develop a sustainable and equitable extractive sector, these challenges must be addressed especially since they have a far reaching impact on human rights. There is need to embed international human rights standards early into the exploration and drilling contracts, impact assessments, due diligence mechanisms and business reporting. This National Action Plan clarifies the Government’s expectation from concerned businesses in this regard.

CHAPTER THREE: POLICY ACTIONS Policy Actions [Page 21] The Government will: i. Introduce a requirement for conducting Human Rights due diligence including the particular impacts on gender before approval of licences/permits to businesses; […]

3.2. Pillar 2: Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights [Page 18] Human rights due diligence is the primary tool that ensures that businesses identify the human rights risks of their activities, take measures to avoid or mitigate them, and where the harm has already occurred, ensure that the victims have access to an effective remedy. This responsibility extends beyond their activities to their business relationships including suppliers and contractors. There is no mandatory requirement for human rights due diligence. Businesses, including state-owned enterprises, have not embraced the practice of engaging those whose rights are most likely to be impacted by their operations. […]

Policy Actions [Page 19] c) Human rights due diligence: Require businesses to identify their human rights impacts including through conducting comprehensive and credible human rights impact assessments before they commence their operations and continuously review the assessment to ensure that they prevent, address and redress human rights violations. Such impact assessment should involve meaningful consultation with potentially affected groups and other relevant stakeholders and include particular gendered impacts.

CHAPTER FOUR: IMPLEMENTATION AND MONITORING 4.1. SUMMARY OF POLICY ACTIONS [Annex]

ANNEX 2: LEGISLATION PROPOSED FOR ENACTMENT OR AMENDMENT

|

Migrant workers

| CHAPTER TWO: THEMATIC AREAS OF FOCUS

2.4 Labour [Page 12] It is imperative that the labour market is regulated to ensure compliance with constitutional, legal and international standards. Several SDGs and ILO core conventions cover various aspects of working conditions including decent work and economic growth, reduction of inequality, quality education and gender equality. The SDG targets include: […] 8.8 (protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers, including migrant workers, in particular women migrants, and those in precarious employment) […] During the stakeholders’ consultations the following concerns were identified: 4) Lack of effective regulation of recruitment agencies for migrant workers […]

CHAPTER THREE: POLICY ACTIONS 3.1. Pillar 1: The State Duty to Protect [Page 17] Policy Actions The Government will: vii. Sensitise relevant sections of the public especially women and other marginalised and minority groups on – a) Land laws, including resettlement and compensation frameworks; b. Labour laws and the rights of migrant workers; and c) Environmental laws and standards;

3.2. Pillar 2: Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights b) Human Rights Policy commitments [page 18-19] The Government will: ii. encourage recruitment agencies to provide any required repatriation, legal and psychological support to migrant workers who have suffered or been subjected to abuse abroad;

CHAPTER FOUR: IMPLEMENTATION AND MONITORING ANNEX 1: SUMMARY OF POLICY ACTIONS

|

National Human Rights Institutions (NHRIs)/ Ombudspersons

| CHAPTER THREE: POLICY ACTIONS

3.3. Pillar 3: Access to Remedy Policy Actions [Pages 19-20] A) State-based judicial and non-judicial remedies The Government will: iii. Provide training and support to the judicial, administrative and oversight organs on business obligations in respect of human rights. Priority will be given to the following institutions:

CHAPTER FOUR: IMPLEMENTATION AND MONITORING [page 22] To ensure that the measures proposed in this NAP are implemented, there shall be a NAP Steering Committee overseen by the Department of Justice and the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights. The Implementing Committee will consist of representatives from the following institutions: 6. Kenya National Commission on Human Rights

ANNEX 1: SUMMARY OF POLICY ACTIONS

|

Read more about National Human Rights Institutions (NHRIs)/ Ombudspersons

Non-judicial grievance mechanisms

| CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION

Objectives of the NAP [page 11] The objectives of this NAP are: 4) To offer a roadmap of strengthening access to State-based judicial and non-judicial remedies for victims of business-related harm.

CHAPTER TWO: THEMATIC AREAS OF FOCUS 2.6 Labour [Pages 13-14] During the stakeholders’ consultations the following concerns were identified: 6) Lack of effective remedies for victims of labour-related grievances resulting in high prevalence of unresolved labour-related grievances. A weak enforcement mechanism, in particular inadequate number of state labour inspectors and the lack of effective operational level grievance mechanisms were also cited as contributing factors.

2.7 Access to Remedy [Page 15] Despite […] legal protections, the community consultations conducted as part of the NAP process revealed structural and procedural barriers to access to remedy, including: iv. There have been instances where human rights defenders who have lodged cases against businesses, especially land and environment grievances, have reportedly faced death threats and other forms of intimidation which they hardly report to authorities. Such hostility may instil fear in others who may wish to lodge complaints, robbing communities and individuals of the protection that the law could have offered against business-related abuses; and v. The capacity of the administrative tribunals to offer non-judicial remedies is often limited by lack of personnel to conduct proper outreach outside of urban centres and the technical capacity to understand emerging and complex issues.

Most businesses have a relatively low understanding of their human rights responsibilities resulting in lack of engagement with employees, local communities and other stakeholders on how to ensure that they respect human rights and provide a remedy for violations. Business associations stated that they lack proper guidance on establishing credible operational-level grievance handling mechanisms.

CHAPTER THREE: POLICY ACTIONS [T]he third part relates to Pillar 3 of the UNGPs and contains policy actions to strengthen access to state-based judicial and non-judicial remedies on the one part and thenon-state-based [sic.] grievance handling mechanisms on the other.

3.2. Pillar 2: Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights [Page 18-19] Pillar 2 of the UNGPs states that businesses should respect human rights wherever they are operating. This is achieved by ensuring that they avoid abusing others’ rights and where harm has already occurred, taking steps to remedy the harm. Policy Actions e) Cooperation on access to remedies: Require businesses to cooperate with government agencies and other stakeholders in facilitating remedies for business[1]related human rights violations. This includes actively participating in policy discussions on access to remedy and adopting policies that enhance access to remedy.

3.3 Pillar 3: Access to Remedy [Pages 19-20] Access to an effective remedy guarantees victims of business-related human rights abuse with predictable avenues for complaints, adjudication of their grievances, an opportunity for the other party to present its case and a fair remedy based on the merits of the case. Additionally, it ensures that remedies are relevant and proportionate to the abuses, including orders to cease ongoing abuses. According to the UNGPs, State-based judicial and non-judicial mechanisms should be the primary avenue for accessing remedies by victims of corporate abuses. However, victims should also have access to operational-level grievance handling mechanisms established by businesses, where workers, local communities and civil society advocates acting on behalf of individuals and communities negatively impacted by businesses may lodge their complaints and receive a just outcome such as compensation, guarantee of non-repetition by the offender, apology, restitution and rehabilitation.

A) State-based judicial and non-judicial remedies [Pages 20-21] Policy Actions The Government will: ii. In line with Article 159 of the Constitution, promote the use of Alternative Dispute Resolution mechanisms in dealing with disputes between businesses and those allegedly harmed by their operations; iv. Improving access to information on available judicial and non-judicial mechanisms involved in the resolution of business-related abuses as a measure of promoting access to justice. Such information should be made available in all counties and provided in a manner accessible to vulnerable groups; vii. Increase the capacity of the labour inspection department to handle labour-related grievances, including through: